Blog posts

Blog posts

Explore Origins of the Dunning Kruger Effect (with 6 Life Sciences Insights).

Newristics

Newristics

26 Dec 2023

26 Dec 2023

Optimize Pharma GTM communications

Innovative messaging market research

Analyze messaging with algorithms

Source for pharma insights and updates

Pharma's top behavioral science source

Newristics

Newristics

26 Dec 2023

26 Dec 2023

The Dunning Kruger Effect definition is a cognitive bias that leads people to over or underestimate their abilities compared to their actual skill set. It explains the gap between one’s confidence and competence and sheds light on how some people can be irrationally overconfident while others can be irrationally humble.

Normally, you expect someone’s confidence level to be in line with their competence level, but every now and then, you come across situations in life when someone feels very confident about a subject but lacks even the basic competence needed. Dunning Kruger Effect offers an explanation for why people sometimes behave this way.

Let’s use a few everyday examples to understand the Dunning Kruger Effect. Many of us might have tried to play a musical instrument in school and given it up after a few years. Someone new to a musical instrument might think they can master it quickly even though they can't even play one note in its purity.

On the other hand, an actual maestro of that same instrument might tell you that they have barely scratched the surface of their understanding of that instrument and the longer they play it, the more they realize that they don't know much.

Neither one makes sense right? One group is overconfident and under-competent and the other one is the opposite.

Sports is another everyday life activity where the Dunning Kruger Effect shows up. An amateur athlete may think that they understand all the nuances of the sport while a pro may be very humble and might say something like, “I am just trying to build better habits and make some improvements to my game every day.”

Researchers have also looked at the Dunning Kruger Effect in high school sports coaching. When 94 high school volleyball coaches completed an assessment of coaching ability, the results supported the generalization of the Dunning Kruger Effect. They showed that when split into 4 quartiles from smallest to largest, coaches in the lowest quartile had significantly higher confidence than competence while those in the highest quartile had significantly lower confidence than competence.

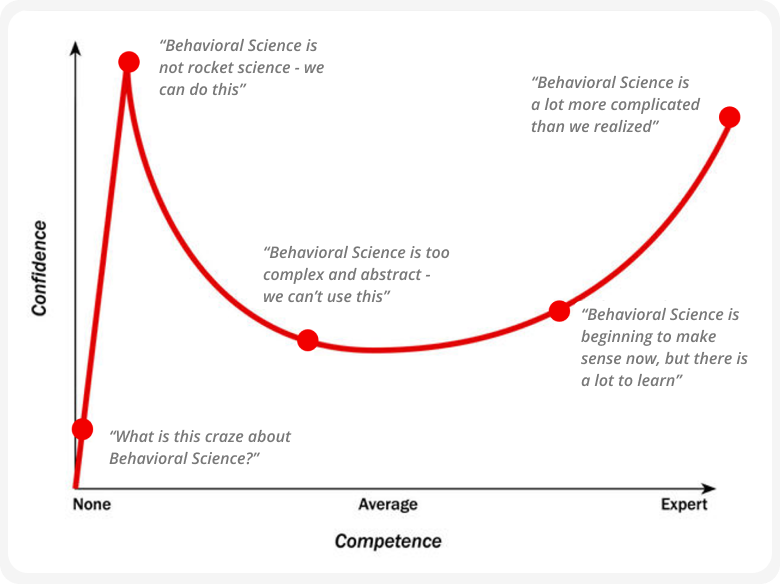

Dunning Kruger Effect is based on a bimodal relationship between one’s confidence and competence (Figure below). On one extreme, we can feel very confident about a certain type of task or activity even when we have little to no competence in it. On the other extreme, sometimes we can doubt our abilities even though we have actually gained significant skills and competence.

Ironically, as competence increases, confidence decreases, perhaps because now you know that you don’t know everything, and even more importantly, you might realize that everything is not knowable. Eventually, when one achieves subject matter expertise, confidence increases and reflects a truer picture.

In psychology, the four stages of competence, or the "conscious competence" learning model, relate to the psychological states involved in the process of progressing from incompetence to competence in a skill. AKA the hierarchy of competence, the four states of competence show the relationship between awareness and competence and how that affects the learning and mastery of a new subject. The four stages are:

| Conscious | Unconscious | |

|---|---|---|

| Competence |

Conscious incompetence

Aware of what we don’t know, but we haven’t taken any steps to learn more. |

Conscious competence

Actively learning and acquiring knowledge about a subject. |

| Incompetence |

Unconscious incompetence

Ignorant of what we don’t know |

Unconscious competence

Mastered a subject to the point that we may forget or take for granted how much we truly know |

Individuals who are in the first stage of competence, i.e. ‘unconscious incompetence’ are most affected by the Dunning Kruger Effect. When you don’t know what you don’t know, the Dunning Kruger Effect says you are actually more likely to feel confident in your knowledge than others who are at higher stages of competence.

In the 1990s, David Dunning and Justin Kruger, professors of psychology at Cornell University, sought to understand whether incompetent people were unaware of their incompetence. Dunning and Kruger performed a series of four experiments that tested whether people hold overly optimistic views of their abilities in social and intellectual domains. They explained these overestimations in abilities as a dual burden: these participants come to misinformed conclusions that result in poor choices, but also their lack of awareness depletes their metacognitive abilities to understand it.

Across all four studies, the researchers found that participants scoring the lowest on tests of humor, grammar, and logic overestimated their test performance and ability. As the participants' skills increased, their metacognitive abilities increased, and they realized the limitations of their performance.

Since the 1999 study, the Dunning Kruger Effect rapidly gained popularity in academia, was cited 8,500 times in scholarly publications, and is the subject of empirical research across fields. Today, the Dunning Kruger Effect has become one of the most popular and well-known theories in psychology. There are 2.1M search results for the Dunning Kruger Effect and an endless supply of memes.

Dunning Kruger Effect has even worked its way into mainstream media, where people use it as an insult against those whom they believe to be expressing incorrect opinions. Now, it's even found in non-educational contexts (movies, TV shows, documentaries, etc.) More recently, the popularity of Dunning Kruger Effect can be credited to social media and the ability to publicly and shamelessly defend our views on any hot-button issue on social media platforms.

Maybe you’ve seen the popular action-packed, thrilling drama comedy series on Netflix called The Recruit which featured the Dunning Kruger prominently in one of the episodes.

In a comical scene, two criminals quip with each other, one calling the other out for thinking themselves as smarter than the other bad guys

When he tries to flee from her, she chases him down in the parking lot, beats him up, and then snaps at him with:

“Who is the Dunning Kruger now, dumbass?”

This 11-second scene captures the pop-culture adoption of Dunning Kruger Effect and the popularity of the “dumb people don’t know they are dumb” narrative in society. Dunning Kruger Effect has become a passive-aggressive way of making fun of the less educated or informed.

Even before Dunning Kruger Effect was discovered, behavioral science already offered explanations for several psychological and cognitive heuristics and biases that lead to irrational behaviors similar to the ones explained by Dunning Kruger Effect:

Optimism Bias - Decades of research in behavioral science have established Optimism Bias as a valid phenomenon influencing our decision-making. Optimism Bias says that humans are sometimes biased to be more optimistic and hopeful than they should be. If they were to make mostly rational decisions using facts, data, or logic, humans would probably realize that they should temper down the false hope in their decision-making.

As a result of Optimism Bias, we can sometimes think that we will perform/fare better at a task than others even though there is no evidence to suggest so. Other times, we expect to perform better in the future than we have in the past or perform better than the average. Optimism Bias accounts for an important foundation of the Dunning Kruger Effect.

Overconfidence Effect - The Overconfidence Effect is a cognitive phenomenon that gives us false confidence about our capabilities. We feel confident that we can be successful under difficult circumstances, even when we lack control that would justify the high level of irrational confidence we have.

Non-Regressive Predictions - To the extent, every decision we make in life involves a prediction about the future, Non-Regressive Predictions is a judgment error that makes us forget about the fact that most events in life are normally distributed and there is regression to the mean.

Non-regressive predictions are predictions that are many standard deviations away from the mean and we forget to take into account that such predictions should be extremely rare. For example, are there some piano prodigies who literally picked up the instrument as soon as they played it? Maybe, but they may be 0.00001% of all piano players and most of us should not expect to be one of them.

There has been a lot of talk recently about the validity of Dunning Kruger Effect and whether it's even real or not. Some researchers have tried to reproduce the original research and have not been as successful in producing similar results.

Just three years after the seminal 1999 study by Dunning and Kruger, Dr. Phillip Ackerman and colleagues simulated the study and found that even randomly generated data created competence vs. confidence relationship curves similar to the original study. If the Dunning Kruger Effect can be replicated by using random data, does it suggest that the effect may not really exist and may be a fallacy of research?

In 2016, Dr. Nuhfer and his colleagues conducted research to study the Dunning Kruger Effect. The team used randomly generated results for self-assessment and performance and once again produced similar relationship curves to those of Dunning and Kruger. This brought forth 3 main claims against the Dunning-Kruger:

Other academic critics have taken issue with the Dunning Kruger Effect due to regression at the mean (regression of the mean only occurs when we track measurements over time). The problem with this is by definition, the Dunning Kruger Effect is not measured over time, and self-assessment and performance are different measurements and cannot be lumped together.

Supporters remain counterarguing that Better-than-average assumes statistical average - not what socially one considers an average person. Despite the controversy, Dr. Dunning and Dr. Kruger were awarded co-winners of the 2023 Grawemeyer Award in psychology for their work identifying this cognitive bias, the Dunning Kruger Effect — publicly reaffirming its validity.

Some new research from neuroscience might be able to shed light on the Dunning Kruger Effect.

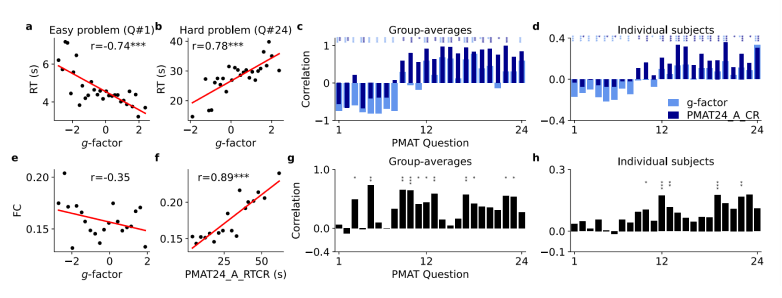

In a fascinating paper out of Europe, researchers simulated brain models that have been trained on data from individuals with different intelligence levels. The goal was to study how people across a range of cognitive abilities make decisions differently. This research paper sheds new light on how people of different cognitive abilities make decisions, potentially supporting the foundational concept behind the Dunning Kruger Effect.

Image Source: DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-38626-y

Image Source: DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-38626-y

The findings were very interesting and counterintuitive. More intelligent people completed simple tasks faster than others but were SLOWER when completing complex tasks or making complex decisions.

The brains of intelligent people had more connections or SYNCHRONY between different parts of the brain, which prevented them from jumping to conclusions when making complex decisions. They didn't make complex decisions until the pre-frontal cortex of the brain had a chance to pitch in and contribute.

While this research was not designed to support or refute the Dunning Kruger Effect, it does shed some light on its existence. If your brain has low synchrony, it can jump to the conclusion that you can master the flute quickly. Conversely, brains with high synchrony can think about the complexity of playing one single note on the flute for years!

Earlier in August 2020, Alana Muller and colleagues conducted a study to produce the Dunning Kruger Effect through a test of item recognition while electroencephalography (EEG) was recorded. Throughout the task, participants were asked to estimate the percentile in which they performed compared to others.

Findings suggest that humans use different cognitive processes while assessing their performance - adding to the literature on Dunning Kruger Effect. It is the first physiological measurement of the Dunning Kruger Effect, sets the stage for further research using the replicable paradigm, and extends the research of the Dunning Kruger Effect to episodic memory task items and source memory confidence measurements.

There is room for continued research on the Dunning Kruger Effect leveraging advancements such as MRI and EEG to eliminate the need for controversial self-assessments.

If the Dunning Kruger Effect is real, we are probably all subject to using it for some decisions in life. Are there some areas of your life where you feel you know a lot even though your knowledge level is superficial at best?

How about personal investing? There is a lot of information and media content available on investing that can give us a false sense of confidence that we have the expertise needed to take risks. Latest consumer fintech platforms like Robinhood can make it very easy to place trades and make investments, which would typically require going through a financial planner or broker in the past.

Dunning Kruger Effect can easily influence investing decisions for the worse and result in major losses that people weren’t prepared for.

Dunning Kruger Effect is easily found on social media platforms as well. Many young people may think that they can become a famous YouTubers and influencers and may not realize how much production and preparation goes into creating videos that garner millions of hits.

There are probably many examples of Dunning Kruger in, and all around us. Unless we proactively check our decision-making, we are as likely to fall prey to the Dunning Kruger Effect as anyone we know. Here is a checklist that can help us de-bias against this effect: